Embroidery as an Agent of Cultural Memory

Sitting in my apartment sewing while also working for MAD’s Curatorial department remotely has been a lived paradox; a twenty-first century method of working paired with the age-old custom of a woman taking up a needle and thread. Needlework and embroidery is a part of my Latvian heritage that I have been actively researching. Motivated by the making and wearing of Latvian folk dress in post-World War II refugee communities, I am examining embroidery and weaving as a strategy for maintaining cultural memory in exile.

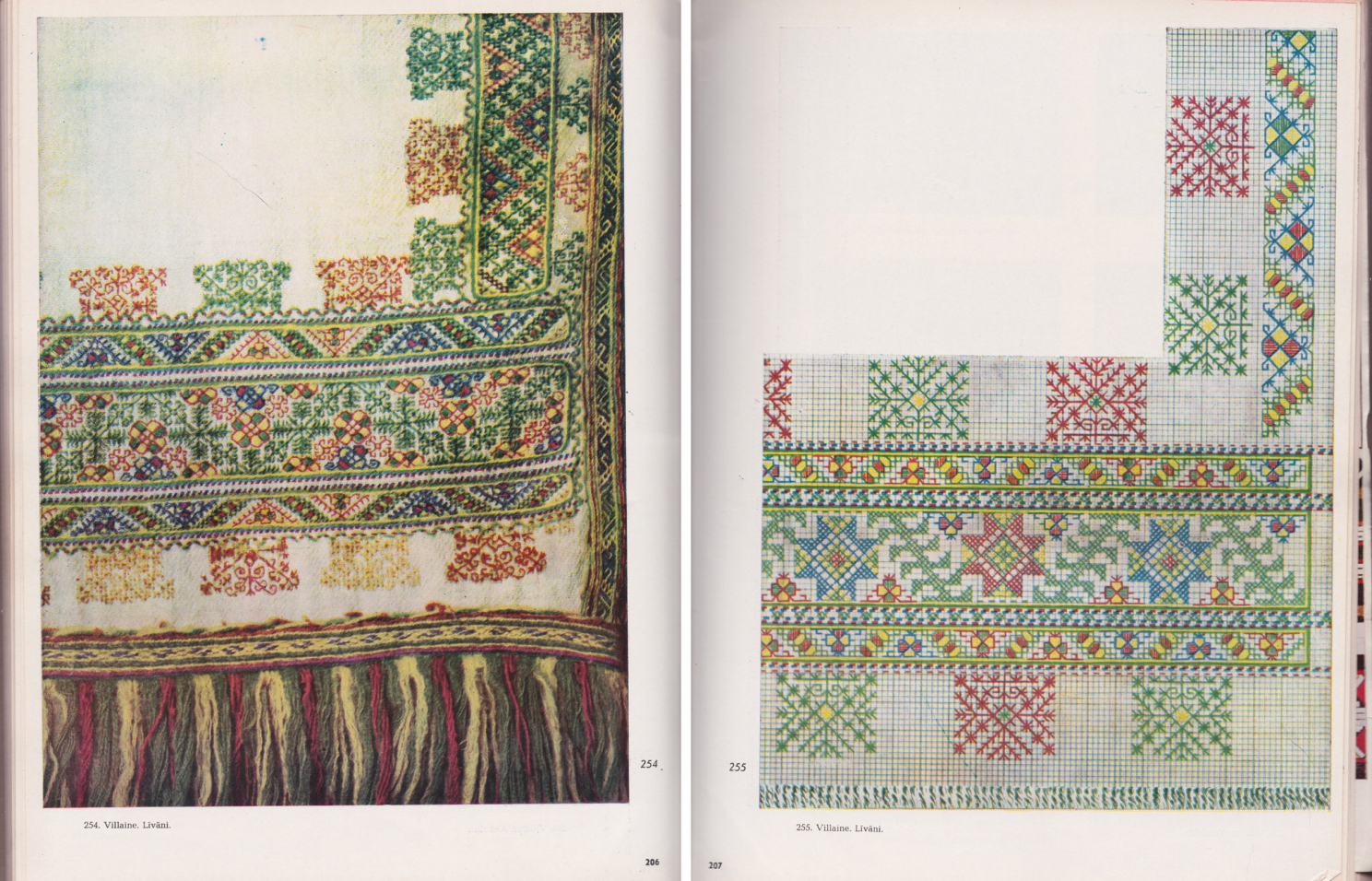

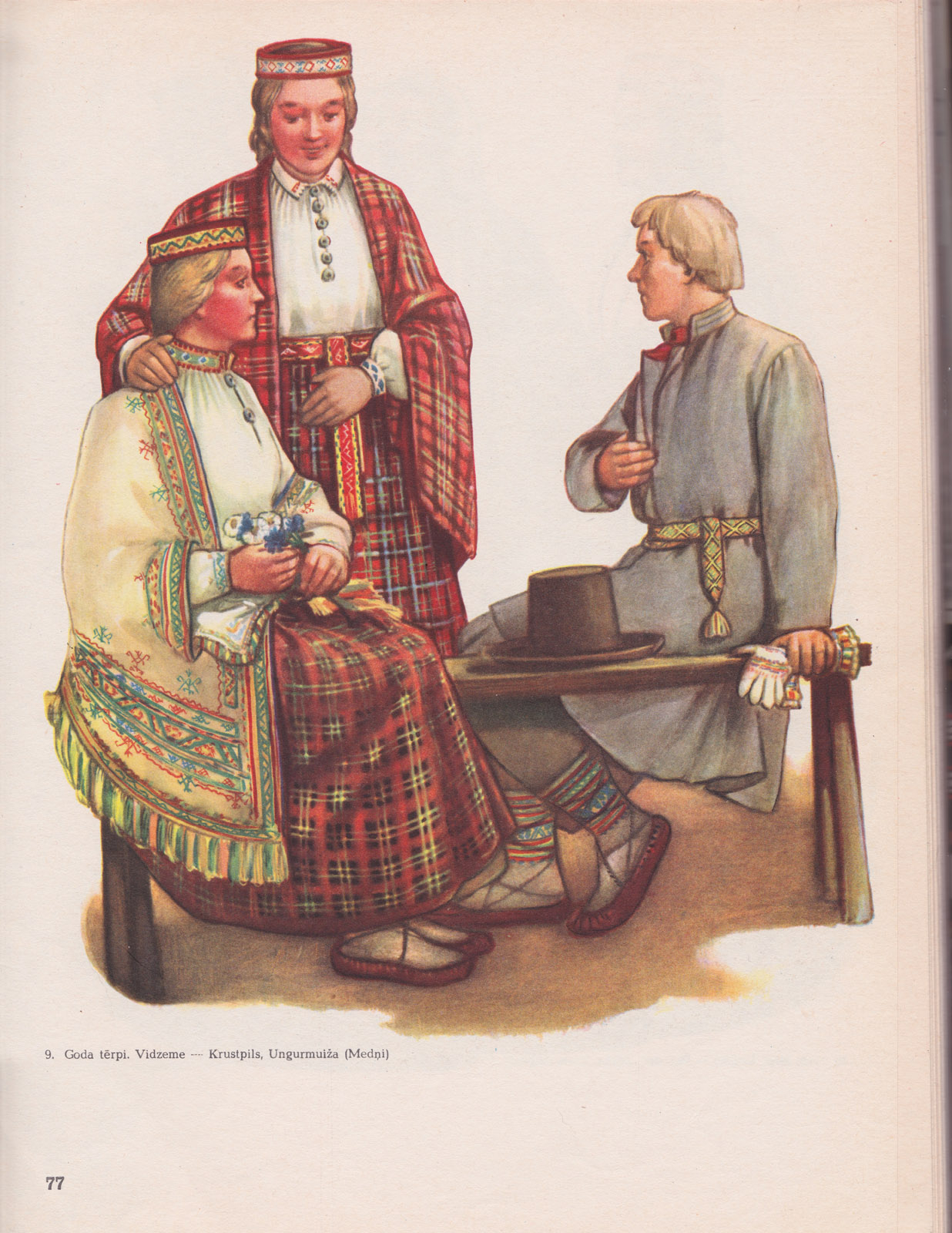

My paternal grandmother, Herta Jekabsons, was born in Latvia and emigrated to the U.S. after World War II, bringing with her a devotion to traditional crafts. I have been able to explore her personal history and connections to my research through my father's old family records. On a trip home earlier this year, I came across a book undoubtedly belonging to Herta. The bookmarked pages contained vibrant, detailed regional illustrations of the embroidered shawls, blouses, woven belts, and skirts, as well as variations of traditional brooches and crowns that encompass Latvian national dress.

Craft traditions, including embroidery, can be dated to the early Middle Ages and were an important part of Latvian national identity in the short period of independence between the two World Wars. During World War II, approximately 120,000 Latvians were exiled from their homeland following multiple invasions by Soviet and German forces. Included in this number were my grandparents, who fled Soviet persecution, bringing with them my aunt and young father. Committed to maintaining the traditions of the Latvian nation outside of its occupied borders, my grandmother taught traditional crafts, including embroidery and knitting, to children of refugees. The book I had uncovered was probably sent from family or friends living in Soviet Latvia and a reference for Herta’s own work, much of which she sold after emigrating to America. For my grandmother and many other Latvian refugees, teaching the Latvian language and crafts in exile communities was a very important method for keeping the culture alive while their native country was under Soviet control from 1945-1991.

Cross-legged on the floor of my father’s office, I pored over drawings of national dress for my grandmother’s Scout troop, which she led in Displaced Persons camps in Allied-occupied Germany. Coming across a folder with a decidedly 1960s floral pattern, I opened the cracking cardboard and encountered her Latvian embroidery patterns from the family’s early years living in California. These forms and symbols, derived from pre-Christian pagan tribes, are copied over in colored pencil, Xs, and other corrections marks, clearly worksheets from her lessons. The content and teaching tools my grandmother created connect to larger histories of teaching national craft forms from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to the present day.

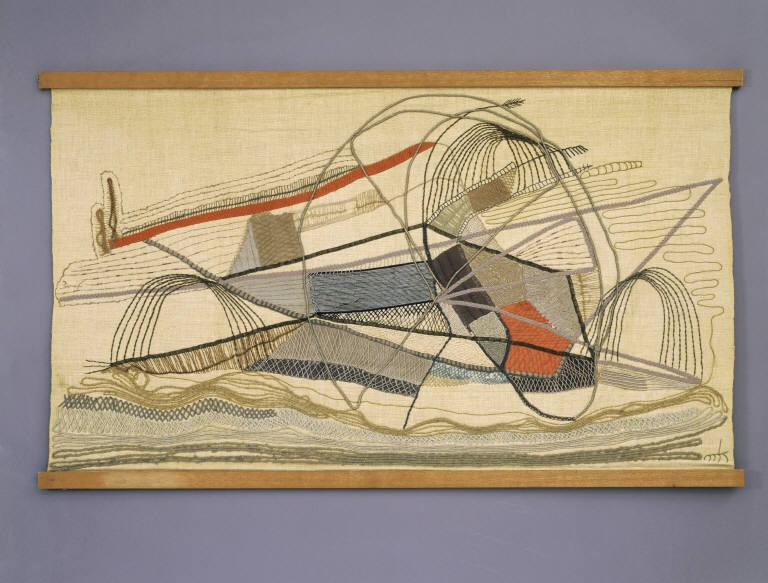

When I began working on this project, my curatorial colleagues aptly pointed out the presence of the themes of migration, displacement, and nostalgia in the embroidery work of two artists with histories at MAD, Mariska Karasz and Jordan Nassar (Conversations like these are among the things I miss most about working in the MAD offices!) Karasz created one of the first works to enter the Museum’s permanent collection. Her 1957 work, Danubian, titled after the river that flows through the artist’s homeland of Hungary, is an imaginative, embroidered depiction of the entirety of the river system.

Karasz learned embroidery as part of her schooling as a young girl living in Hungary in the early twentieth century. After immigrating to New York at the outbreak of World War I with her mother and sister, she found work as a fashion designer following her studies at the city's famed Traphagen School. Karasz’s designs often combined Hungarian folk motifs with contemporary Western styles, especially in the embroidered treatments of her garments. She published several books on embroidery, and by the 1940s the artist had developed a less commercial-based view of the craft, stating in her 1949 book Adventures in Stitches: A New Art of Embroidery :“embroidery is to sewing what poetry is to prose.” Moving to work on flat panels of fabric, the subjects of her work ranged from abstract to figurative. Karasz’s early upbringing in Hungary introduced her to the medium as a part of a national heritage. Her continual engagement with embroidery as an artistic act allowed her to expand and develop her own knowledge and ethos.

Jordan Nassar, a finalist for the 2018 Burke Prize, is a New York-based artist working primarily in hand embroidery. A second generation Palestinian American, his practice is rooted in traditional embroidery from the region. Nassar has been able to return to Palestine to work with and learn traditional techniques from women who continue to embroider. In creating his patterns, Nassar also sources imagery from embroidery pattern books from various regions and cultures, including Semitic, Islamic, Slavic, and Native American.

The works shown in the Burke Prize 2018 exhibition are composed of intricate needlework patterns and color blocking. Recalling a landscape from topographic and frontal viewpoints, these works illustrate a homeland evoked in family stories and in conflict with reality. His recent Night series is centered around a nineteenth-century traditional Palestinian dress, encased in a wooden display. Apart from the heavily decorated, formal comparisons to the bright embroidery on dark fabric, the antique dress serves as a source for the series. The connection between folk costume and embroidery makes evident the interdependent relationship of craft and traditional clothing ,and clarifies their role and shared histories in maintaining cultural memory.

Viewing these works in light of my own connections to traditional embroidery, it is clear that a central tenant for the survival of this medium from generation to generation is education. In cases of artists and makers like Karasz, Nassar, my grandmother, and those who are immigrants themselves or first- or second-generation Americans, teaching created space for cultural practices to evolve and persevere. This work extends beyond techniques in classes or in publications and allows for the significance of traditional embroidery work to becme a connective thread between their heritage and their artistic life.

While Herta undoubtedly learned Latvian folk embroidery techniques and forms in school during the 1920s as part of the young country’s new curriculum, Mariska Karasz was taking part in similar activities in Hungary related to Hungarian folk culture. Nassar continues this education-based engagement with the medium in his work with Palestinian embroiderers.

Looking at these two examples from across MAD’s exhibitions and collections reveals a resonating through line of embroidery as a way of making meaning from immigrant and refugee memory. The stories circulating the work of Karasz and Nassar are ever-present in MAD’s history; one does not need to look far into the Museum’s collection to find countless narratives related to nationality, identity, and displacement. My research into my own history has deepened my understanding of the significance of craft in times of war and upheaval and its centrality in maintaining cultural memory.

—Alida Jekabson, curatorial assistant

Further reading

Callahan, Ashley. Modern Threads: Fashion and Art by Mariksa Karasz. Athens: Georgia Museum of Art, 2007

Saca, Iman. Embroidering Identities: A Century of Palestinian Clothing. Chicago: University of Chicago, 2006

Welters, Linda, and Abby Lillethun. Fashion History: A Global View. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2018

Subscribe

Join our mailing list.

Join

Become a member and enjoy free admission.

Visit

Find out what's on view.